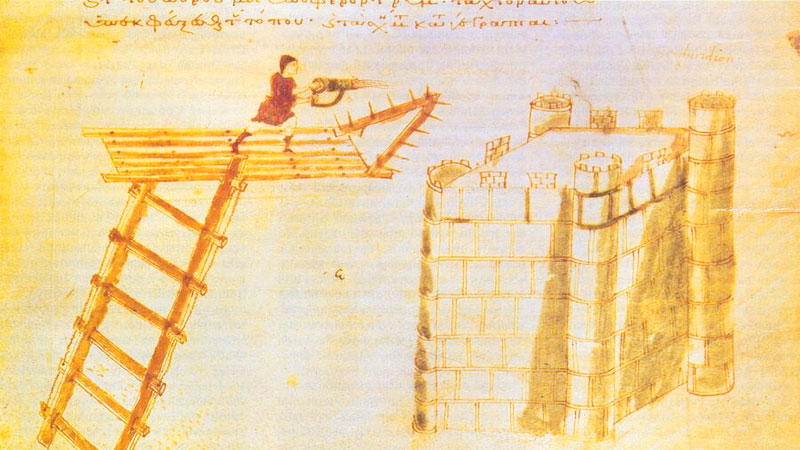

Chemists were able to quickly adopt Greek Fire into a variety of incendiary devices, including projectiles, hand-held devices and a flamethrower. All of them helped to make the Byzantine military victorious in the majority of their battles.

Some of the other Byzantine names for Greek Fire, such as War Fire, Liquid Fire and Sticky Fire, help us to better understand the nature of the mysterious and dangerous substance.

Today, we still do not know exactly how Greek Fire was made or what the chemical composition of the substance was. For a long time, it was assumed that Greek Fire contained a generous portion of saltpeter, a potassium nitrate compound that is akin to gunpowder. The only basis for this assumption was the descriptions of Greek Fire that referred to “thunder and smoke”, which led many to assume the reports were describing an explosion. This claim has been discounted, however, because there is no evidence of saltpeter being used in Europe or the Middle East prior to the 1200s.

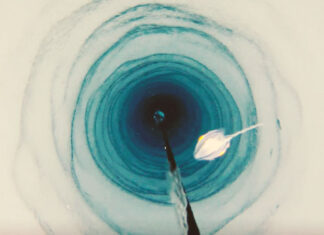

The Roman historian, Titus Livy, in his famous work “The History of Rome”, wrote that Greek Fire was not extinguished by water. He noted that the priestesses of Bacchus could light torches of Greek Fire then plunge them into the water with no effect on the fire. Livy wrote that the reason for this was that Greek Fire was “sulfur mixed with lime”.

The lime he is referring to was most likely a material known as quicklime or calcium oxide. Quicklime was well-known by the Arabs and Byzantines at this time and the material would ignite when in contact with water, making it a viable candidate for Greek Fire. However, the power and intensity often associated with stories of Greek Fire would be difficult to achieve with quicklime.

Emperor Leo the Wise, who wrote “Tactica”, one of the most important Byzantine military works, said that Greek Fire was poured onto the decks of ships and ignited from afar to destroy the enemy’s ships.

If Greek Fire was comprised of quicklime, it would have ignited on contact with ship decks, which are notoriously wet. But what Leo the Wise describes was that the ships were set afire by tossing a flaming grenade or shooting a flaming arrow to ignite the Greek Fire that was already on the ships’ decks.

It is possible the Greek Fire was a petroleum product, maybe even one similar to napalm.

The Byzantines did have access to crude oil from spots around the Black Sea and other parts of the Middle East.

We do know that in the 9th century, the Abbasids people used crude oil as a weapon of warfare. Specially trained soldiers carried copper containers filled with burning oil that was flung into the enemy lines.

An ancient Latin manuscript from the 9th century even seems to give a recipe for Greek Fire that can be used in a type of flame-throwing apparatus.

Most likely, resins, tar, animal fat and pine sap were added to the petroleum to help maintain the fire and to help the fire burn hotter. Since one of the alternative names for Greek Fire was Sticky Fire, one can surmise that it is because of the resin additive.

Other experts believe that Greek Fire may have been calcium phosphide. Calcium phosphide is made by boiling crushed bones and urine over a hot fire in a sealed metal vessel. When calcium phosphide comes into contact with water, a chemical reaction starts that released phosphine which then spontaneously combusts.

While it is chemically possible to recreate this reaction, it is far less intense as the descriptions of Greek Fire.

Although we are not sure how Greek Fire was made, we do know how effective it was as a military tool.

For the Byzantine Empire, Greek Fire was the biggest factor in repelling the Muslim invaders who had attempted to seize Constantinople.

Greek Fire was mentioned as being used in 1099 in a naval battle against the Pisans and during the Fourth Crusade, in the siege of Constantinople in 1203. In fact, the use of Greek Fire is mentioned frequently in several conflicts during the Crusades.

It was its use in medieval times that probably caught the attention of authors such as George RR Martin, Michael Crichton, Mika Waltari and C.J. Sansom, all of whom reference the magical properties of Greek Fire in their writing.